Hiking in the Australian Alps

Hiking practice

Australia is a large continent with just about every type of environment and vegetation you can imagine ranging from coastal, dry and wet forest, arid to semi-arid; and then there’s our sub alpine and alpine regions which make around 1% of the continent.

I’m a big fan of hiking Australia’s drier regions and we enjoy spending time in the Australian alpine regions. While the practice of planning hikes is the same no matter where you are, there are some specific considerations that hiking in Australia’s alpine zones require. This article discusses hiking in Australia’s alpine zones in three season conditions and doesn’t deal with winter time hiking where you’ll experience heavy snow conditions.

Definitions

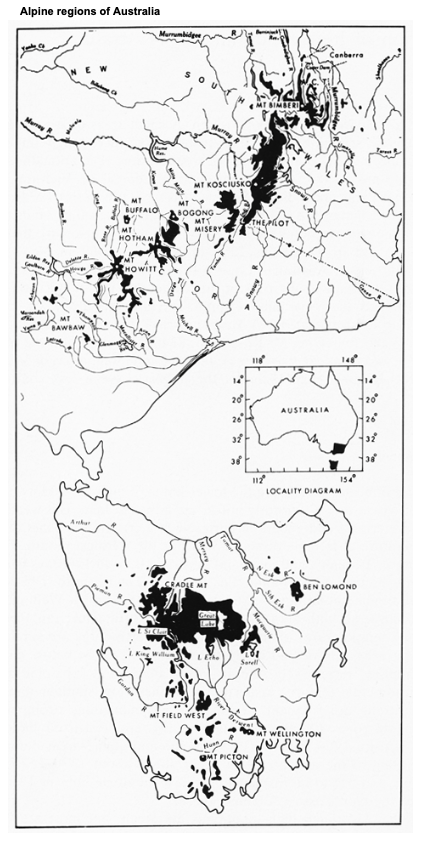

Australia’ alpine regions account for approximately 1% of the Australian landmass. So what defines ‘alpine’, and where is it located from an Australian perspective?

- Sub-alpine Zones

- Sub-alpine areas are those areas 600 – 1,200 metres altitude in NSW, ACT and Victoria and

- Between 300 – 900 metres altitude in Tasmania.

- Alpine Zone

- Alpine areas are defined as those areas which are 1,200 metres or more above Australian height datum (AHD) for NSW, ACT and Victoria and

- Above 900 metres AHD for Tasmania.

Map of the Alpine Zone in Australia (image form the Australian National Botanic Gardens)

Australia’s Alpine character

One thing I would say here is that many people associate the Australian alpine region with mainland Australia but there are also alpine regions in Tasmania as well. The majority of the world’s alpine zones consist of rock mountains; they are often glacier covered and much steeper than what we have in Australia and as such they tend to be bare of soil. In addition our tallest mountain, Mount Kosciuszko, is just 2,228 metres (7,310 ft) above sea level which is relatively low when compared to all the other alpine regions around the world.

For the most part, the Australian alpine zones have a soil covering, which provides an anchor for plants, as well as providing habitat for micro-organisms and invertebrates. These plants and animals then become the food source for many other animals, providing the biological support base for other organisms in the alpine ecosystem. Plants also protect the soil from erosion by providing ground cover so the stability of Australian mountain ecosystems depends on good vegetation cover to maintain the health of the soils.

Because of the shallow soils in these zones combined with low temperatures, frosts and strong winds, plant growth is slow when compared to other Australian vegetation zones. This means that the alpine zones are easily damaged by natural causes and also by heavy/overuse by people. Once exposed, the soils are vulnerable to the weather and more likely to erode which is why you often see designated boardwalks in high use areas.

Summit of Mount Kosciuszko. Approximately 100,000 people a year summit Australia’s tallest mountain – this was a particularly busy weekday around lunchtime

Approaching Mount Kosciuszko Lookout; this wasn’t the summit but a lookout on the way to the summit. This steel mesh helps to protect the sensitive landscape from the heavy foot traffic

1. Temperatures

When most people think about Australia’s alpine regions they automatically think ‘cold’ and in most cases they would be right. The temperatures throughout the year are colder than they are at lower elevations and in most cases the maximum temperatures are much cooler than they are at lower altitudes.

A few years ago Gill and I hiked the summit of Mount Kosciuszko on Christmas Day – the temperature started off at 25 degrees Celcius but by the end of the walk it had dropped to 6 degrees Celcius. We came prepared but a number of walkers, in particular young children were wearing clothing that just wasn’t suitable for the conditions.

A key consideration when hiking in Australia’s alpine zones is that snow can occur in any month of the year. The video below was take in February 2023 when we walked the Cascade Hut Trail. While February is usually snow free in this area of the park, you should always come prepared for very cold/snow conditions even in summertime. If you are camping in the Australian Alps, be prepared for sub zero temperatures at any time of the year.

This video was taken in February 2023 on the Cascade Hut Trail in Kosciuszko National Park. While February is usually snow free in this area of the park you should always come prepared for very cold/snow conditions even in summer

Sea to Summit Flame III sleeping bag – night temperatures in alpine regions can drop below 0 degrees Celcius so come prepared

2. Layering

To cater for extreme changes in temperature you need to come prepared, hypothermia is a major consideration in Australia’s alpine region even outside of snow season, and even in summer if the conditions turn bad.

Everyone’s layering system is unique with most people opting for a 4 layer system. The sun can be quite intense in semi arid and arid landscapes so I recommend wearing long sleeve tops and long pants rather than opting for a T-shirt. Having said that, most people I see on-trail in the high country wear T-shirts in hotter weather but this then means you will need to liberally apply sunscreen throughout the day.

I usually don’t worry about gloves from a warmth perspective on arid and semi arid hikes but in alpine regions I wear lycra fingerless gloves to prevent the back of my hands from getting sunburnt particularly if I’m using trekking poles where the tops of my hands are exposed. Another option is wearing a lightweight long sleeve top with thumb loops, like the Icebreaker Men’s Cool-Lite Merino Long Sleeve Hoodie that also does the same job.

Whatever layering system you use, make sure it accommodates the expected extremes of your trip.

While we’re on the topic of layering and protection from the elements, make sure you keep your head protected from the sun with a broad brimmed hat that provides protection to your neck (see image below), and you also need to protect your eyes with UV compliant sunglasses.

I use a 4 layer system and find it keeps me comfortable in temperatures a low as -7 degrees Celcius up to temperatures in the mid to high 30’s although those high temperatures are less common at high altitude

Sunday Afternoons Ultra Adventure Hat – our hat of choice for hot conditions but also for the Australian Alps where high UV is an issue

3. Avoid the extreme cold

If you’re hiking in Australia’s alpine zones pay very close attention to the weather patterns in the days leading up to your adventure and also pay particular attention on the day(s) that you’re walking. On really hot days try to start early and avoid the hotter parts of the day.

Also, during late Autumn and early Spring the days will be shorter so make sure the distance you’re intending to cover allows time for setting up your camp in daylight.

4. Water

Regardless of the time of the year or the temperature, you should always drink plenty of water when you hike. This is particularly important when you’re heading into arid and semi arid regions. The hotter the weather, the more you will drink:

- In cooler weather conditions (below approximately 20 degrees Celcius) I will drink 1 litre per 10 km walked

- In hot weather I will drink 1 litre per hour (which is roughly 2.5 litres per 10 km). On my longest hot weather day I consumed 8.5 litres of water

- If undertaking a long day hike, you should ‘Camel up’ (i.e. drink a litre or more before you start your hike).

What all this means is that you need to ensure there is either water available on the trail or that you carry enough water to last you until your next water source. Knowing where reliable water sources are is important on every hike and this includes alpine areas.

A few years ago I walked from Kiandra to Tharwa which was the last section of the Australian Alps Walking Track and got caught out when I discovered my usually reliable water sources were dry. Thankfully I had a water filter with me because I ended up drinking from a stock dam – the water could best be described as ‘gelatinous’ (Cow saliva – yuk!).

While the Australian alpine areas have lots of water in Spring, once you hit Summer and Autumn these water sources can dry up depending on the weather conditions. In addition there is a horse issue in some of the alpine national parks so bring a filter!

I use a 3 litre water bladder when I hike and will drink small amounts regularly. If there is any doubt about upcoming water sources, top up every time you come across new water.

Katadyn BeFree with dam water. I had no other water source to use and was very glad I had a water filter with me!

5. UV

Earlier in this article we discussed temperatures and while it doesn’t get as hot in the alpine zones, UV levels are a major issue that most people don’t think about. In fact the higher areas of the alpine zones are up to 2,228 metres (Mount Kosciuszko) above sea level and the UV levels are 24–28% stronger. So while it may not feel hot, the increased UV will mean you will get sunburn and skin damage more easily than at sea level.

This brings us back to layering again. Covering up with long pants, long sleeves, a broad brimmed hat and lightweight lycra gloves are essentials rather than optional. Failing that, apply sunscreen liberally and regularly.

If you’re travelling above the tree line, carry a tarp to provide some shade during daytime. The image below shows our tarp set up – while we could have very easily sat in our tent, the temperature in the walled enclosure (e.g. the tent) was stifling and we preferred the breeze that the tarp allowed.

Escapist Tarp set up below Ramshead Peak in Kosciuszko National Park. When you’re above the tree line there isn’t much shade so to get out of the sun you need a lightweight tarp to provide shelter

Outdoor Research Active Ice Spectrum Sun Gloves. If you’re using trekking poles, sunburn on the tops and backs of your hands can be a real issue. Wearing lightweight fingerless gloves can make a huge difference

The UV radiation in the Australian Alps is pretty high (about 24-28% higher than at sea level). This image was taken before I learnt about wearing fingerless lycra gloves when using trekking poles which expose the backs of your hands to the sun

Time with a sunburnt head. I had a bit of a brain snap on this day in the Australian Alps – I wore a peaked cap rather than a broad brimmed hat and paid the price! It was by no means hot only around 18-20 degrees Celcius but the UV was brutal

6. Lightning strike!

Due to my interest in doing overseas hikes I have always been aware of the impact of lightning in the USA as well as some European countries when travelling above the tree line.

In fact, one hike I have been looking at in Corsica, the GR20, has a known issue with lightening. In the Summer months you need to be off-trail by midday as the lightening storms hit in the afternoon.

While I had always assumed this was a potential issue in the Australian alpine zones above the tree line, no one really seems to talk about it. In reality on average there are around 5 to 10 deaths a year from lightning strikes in Australia and more than 100 people are seriously injured annually. The majority of fatal lightning strikes were found to have occurred in late Spring/Summer, and between noon and 6pm. Of the victims, 7.4% were in tents. A sobering thought for bushwalkers, since all tent poles, whether aluminium or carbon fibre, make for excellent conductors of electricity.(1)

Seamans Hut, Kościuszko National Park

7. Wildlife and vegetation

On just about any hike most people enjoy seeing the local wildlife. In regard to hiking in alpine areas you can really split vegetation and wildlife into two broad groupings:

- Above the tree line

- At the very highest of altitudes there is very little animal life, mainly birds, and the ground coverage tends to be grassy plains.

- Below the tree line

- Once you get below the tree line you start picking up the typical wildlife you would expect on most hikes; kangaroos, wallabies, snakes and birds

- The vegetation, while typically less diverse, is still pretty impressive with one of my favourite plants being the Snow Gums that are usually the last of the trees before the tree line ends.

One other ‘wildlife’ consideration is the wild horse population in many of our alpine parks which creates two issues for hikers:

- The impact they have on the water sources which means you really do need to filter.

- The second is that the stallions mark their territory by piling their droppings on the trail. Sometimes its so bad you can’t avoid walking through it!

Angry Tiger Snake just at the base of the tree. This image was taken in Kosciuszko National Park below the tree line. This snake was sunning itself on the side of the trail – it wasn’t happy about being disturbed and escaped between the two of us hissing as it went

Wild horses in Kościuszko National Park. Over a three day hike I stopped counting when I reached 200

8. Creepy crawlies

There are two creepy crawly’s to consider in Australia’s alpine regions:

- The first are the March flies which will bite you and are capable of penetrating thin tops and even hiking pants. I have even watched one trying to bite through a set of leather hiking boots. These flies are mainly present through our Summer and it’s for these creatures alone that you want to wear long pants and long sleeves. I find they don’t care about insect repellant. Wear short pants and short sleeved tops and you will pay the price!

- The second creepy crawly to worry about are a species of funnel web spiders that live in the Australia Alps. I have never been a big fan of tarp camping preferring a fully enclosed shelter mainly for this reason and have heard enough horrible stories as well as seeing the male spiders on-trail looking for the females. Not so much of an issue above the tree line but definitely something to keep an eye out for when camping below the tree line. Keep your pack and shoes inside your tent but if you can’t, check your shoes before putting them on.

March Fly trying to work its way through my pants. It is capable of getting through long pants if it has enough time

Funnel web spider on Mount Bimberi in the ACT. This photo was taken at an altitude of approximately 1850 metres

Last words

Hiking in Australia’s alpine and semi alpine regions has its own unique considerations but it ranks as some of my favourite hiking. To get the best out of these hikes you won’t have to make to many changes to your typical hiking style but you will need to cater for some specifics.

The main changes I make include wearing lycra fingerless gloves, a broad brimmed hat even when it isn’t hot, and carrying a lightweight tarp in addition to my tent. I will also always cater for snow conditions even when it isn’t forecast. From my perspective, these are only minor changes I make to what I carry and ensure I have a safe enjoyable hike.